November 11, 1973

An article in Parade Magazine describes Watergate as changing the life of Inouye and his family when the senator was thrust into the national spotlight, becoming widely known for his honesty and decency.

TRANSCRIPT:

Washington, D.C., and Honolulu

This past summer when the Watergate hearings reached their apogee, a group of schoolboys ran up to Sen. Ted Kennedy and Dan Inouye.

“I stepped back,” explains the diminutive (5-feet, 6-inch) Democratic Senator from Hawaii, “because I knew from experience that everybody wants Ted’s autograph. But this time it was different. The kids didn’t want his autograph. They wanted mine. I knew then that Watergate had changed my life.”

Ironically, Inouye (pronounced — in-aw-way) vehemently refused to accept a place on the Watergate committee when it was first offered to him. “I tried every way I knew to get out of the assignment.”

But the Democratic leadership insisted. They wanted someone with a Mr. Clean image to investigate the Republicans’ dirty tricks and Inouye has a spotless record in politics. Until Watergate, however, national limelight escaped him.

In 1959, when he arrived in Washington, a freshman Congressman to represent the new state of Hawaii, he was introduced to the venerable and veteran Speaker of the House, Sam Rayburn, then 77, “It’s a very great honor for me,” acknowledged Inouye, “to meet the most famous, widely recognized member of the Congress.”

Speaker Sam took optical inventory of Inouye. “Don’t worry,” the Texan assured him. “You’ll soon be the second most widely recognized member in the Congress.”

Inouye, 35, raised a quizzical eyebrow. “How do you figure that, Mr. Speaker?”

Rayburn replied quickly, “We don’t have too many one-armed, Japanese Congressmen here.”

Prophecy fulfilled

Today, 14 years later, after three years in the House of Representatives and almost two terms in the Senate, Daniel Inouye, has virtually fulfilled the prophecy of Speaker Sam Rayburn, who died in 1961. He has become one of the most widely recognized members of the U.S. Senate.

Owing to his ethnic background (Japanese), the loss of his right arm (in World War II) and his membership in the Senate Watergate Committee, Senator Inouye is instantaneously recognized these days.

Prior to Watergate, he was known mostly in the Senate and within the borders of his own state where he’s always been exceedingly popular. (In 1968 he was reelected by a staggering 83.3 percent of the ballots.)

“Now,” he says, “it’s a different ball game. When I get off the plane in San Francisco, going to or coming from Honolulu, people come up to me and shake my hand. Perfect strangers. They’ve seen me on TV. I’ve appeared on all the networks. I’m constantly called for interviews and speeches. Before Watergate, my exposure quotient was almost zero, at least on the Mainland.

More mail, more work

“Watergate added five hours to my workday, every day. The mail load increased from 200 to 1000. The peak was something like 4000 a day.

“From a family standpoint,” Inouye continues, “Watergate also made a difference. My home telephone numbers in both Washington and Hawaii are listed. My son, Dan, 9, used to enjoy answering the phone. But since Watergate I grab the phone, because although most of the phone calls are courteous, there are now some that are rather hateful. I don’t want Danny picking up the receiver and getting barraged by obscenities. Until Watergate I never got obscene calls.”

Before Watergate, however, Inouye was never considered a possible Democratic Vice Presidential candidate; now he is. There is no mentioned Democratic Presidential hopeful — Kennedy, Mondale, or Humphrey — who does not hold Inouye in a favorable running-mate light.

A war hero, a Methodist, a minority ethnic member, a superb campaigner who has never lost a race, a politician unsullied by the slightest stain of scandal, Inouye is regarded as a political plus. At 49 he is young, vigorous, growing, an exemplary U.S. Senator. The largest campaign contribution he ever received was donated by Mary Lasker, widow of the advertising tycoon, Albert Lasker.

“It was in 1959,” Inouye narrates, “right after Hawaii was accorded statehood, and I announced my candidacy for the House of Representatives. One day I received a $5000 check from New York City from Mary Lasker. I had never met a woman named Mary Lasker.

“But there was her check and a one-line letter. It said, ‘I wish you all the best.’ That’s all. I wrote a letter thanking her, but I never got a response. Three years later I finally met Mrs. Lasker, and I thanked her. ‘Oh, don’t mention it,’ she said. Incidentally, she never asked me for a single favor.”

‘What I’d like…’ Inouye insists, “I do not want to be Vice President of the United States. I have never in my wildest dreams seen myself in that role, and I don’t see it now. What I’d like are two more terms in the Senate. Nothing more. By that time I would be 62. My son would be 22, capable of earning his own living.

“I’d like then to go back to Hawaii with my wife Margaret, perhaps teach a seminar in political science, maybe write a book on government. I’ve seen a lot of books on government, but I’ve yet to see one that would give a real insight into what goes on around here. For example, just look at how I got appointed to the Watergate Committee.”

Originally, Mike Mansfield, the Senate Democratic Leader, decided that no Democrat who was a lawyer should be assigned to the Watergate Committee. Immediately that eliminated half the Democrats in the Senate. His second restriction was that no senior Senator who chaired a committee, Fulbright of Foreign Relations, Eastland of Judiciary, McClellan of Appropriations, Jackson of Interior, should be assigned, because these Senators already carried too heavy a workload. A third restriction held that if any Democratic Senator had ever aspired to the Presidency or had been mentioned seriously for it, then he, too, was disqualified.

“It finally came down to four of us,” Inouye says half jokingly, “myself, Montoya, Talmadge, and Sam Ervin. And even then, Mike Mansfield had to scrap the lawyer restriction, or he couldn’t have gotten anybody.”

All for the best

Inouye, of course, is now happy that he accepted the Watergate chore. It not only afforded him maximum TV exposure and new prestige during his start-up campaign for a third term, but, he says, “I believe what the committee disclosed will have a lasting effect on future Presidents and their advisers. It will help reform the campaign practices of the nation.”

The Senator, who spent $60,000 in his first Senatorial race in 1962 and $70,000 in 1968, says that he personally has learned a great deal from the Watergate hearings.

“Having been in politics since 1954,” he explains, “I wasn’t particularly naive about big money, but I never dreamed that so much — $60 million of Republican funds and about $37 million of Democratic funds — was involved in the ’72 campaign.

“I was also not aware of the dirty tricks, the espionage, the arm-twisting, the shady, scurvy, slimy tactics, the corruption of young men by older men who preached law and order. And this bugging of telephones! It’s been shocking! And what a horrible commentary on our democracy!

“I’m sad to say,” he asserts, “that many of us in the Senate just assume that our phones are tapped. I operate on that basis. You notice that the doors to my office are always open. If you come into my file room, you’ll notice a whole bank of filing cabinets. They’re all open. No one has to jimmy them. The only time we lock our doors is at night. In Honolulu, the same thing. My desk is set up in such a way that as soon as one opens the door they can see me. I make myself accessible, and if your discussion is unfit for my secretary’s ears, I don’t want to hear it.

Names and amounts

“I recently had a campaign fund-raiser dinner in Honolulu. I released all the names and addresses of the contributors and the amount each had contributed, and I’m going to insist upon that procedure.

“At a time when the Vice President of the United States has resigned and the President himself is under fire and the whole political system is under a dark cloud of suspicion, I believe that legislators, politicians have to reassure the people that honesty and openness and decency are still the character ingredients of the men they elected.”

Daniel Inouye, the first Nisei ever elected to the U.S. Senate, feels a very special obligation to the American way of life even though he has been a victim of its prejudices.

Pre-war Hawaii, run by the descendents of the American missionaries who had stolen, connived, and intermarried into Hawaiian property, was full of bias. It was only through the intervention of Franklin D. Roosevelt that the War Department after Pearl Harbor permitted 1500 Nisei volunteers to join the U.S. Army, form the 442nd Regiment combat team and die in Italy in horrendous numbers to prove their loyalty. Eventually some 33,000 Nisei saw action in Europe.

What price glory?

In 1946, Capt. Daniel Inouye was returning to Honolulu. Heavily decorated with rows of campaign ribbons, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Bronze Star, the Purple Heart — small compensation for the loss of his right arm in a gallant assault against a German machine-gun bunker in Italy — Inouye walked into a San Francisco barber shop, his empty right sleeve pinned to his tunic. He asked for a haircut.

“We don’t serve Japs here,” the owner snapped.

Twenty-seven years later, Inouye was again to hear the “Jap” racial slur; this time from John J. Wilson, the Watergate lawyer for President Nixon’s two closest advisers, Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, the latter now under indictment for perjury and conspiracy. Subsequently, attorney Wilson apologized, and Inouye generously accepted the apology, attributing the “Jap-crack” to the hot climate generated by the Watergate hearings, in which the Senator had muttered under his breath, after hearing Ehrlichman’s testimony, “What a liar.”

Dan Inouye was born in Honolulu on Sept. 7, 1924, the son of poor Japanese immigrant parents. His mother was the orphaned daughter of a Hiroshima family whose members had signed up for contract labor on the sugar plantations of Hawaii. His father came to Hawaii from Japan with his parents at the age of 4.

Named after a Methodist minister, young Dan was raised in poverty. He attended Honolulu public schools, was graduated from McKinley High School, then named “Tokyo High,” because most of its students were Japanese.

After Pearl Harbor

When Pearl Harbor erupted, Inouye was 17. At the outset of the war, all Americans of Japanese ancestry were discharged from National Guard units in Hawaii and rejected by the Selective Service system. Sometime later, President Roosevelt declared, “Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race and ancestry.” He ordered the War Department to accept a limited number of Americans of Japanese descent. Dan Inouye, 18, a freshman in pre-med studies at the University of Hawaii, was one of those. Sent to Italy where he won a battlefield commission as a second lieutenant “because I learned how to kill well,” he was seriously wounded by a German rifle grenade at close range, spent 20 months in various Army hospitals after losing his right arm.

Meets future wife

Returning to Honolulu, he abandoned hopes of becoming a surgeon and entered the U. of Hawaii as a pre-law student. There he met Margaret “Maggie” Awamura, daughter of a Honolulu jeweler who had done her undergraduate work at Hawaii and had also taken a master’s degree at Columbia University.

“I met him via a phone call,” Mrs. Inouye says of her first date with her husband. “He called to say hello and asked me for a date, a dinner-dance at Fort Shafter with some of his veteran friends. I said, yes, and on the second date he took me out to dinner and proposed. I said yes again.

“We got married in 1949 and went off to Washington, D.C., where I worked as a secretary in the Navy Department while Dan went to George Washington University Law School. Then we returned to Honolulu where Dan practiced law and went into politics. It was a very propitious time. For years the Republican Party had dominated politics in the islands, but after the war the Democratic Party opened its arms to the returning Nisei and other underprivileged groups, and Dan ran into them.”

Inouye ran for the territorial House of Representatives in 1954, was elected majority leader at age 30, held the position until 1958 when he was elected to the Hawaii Senate.

A year later when Hawaii became a state he won election to the House of Representatives and then re-election to a full term in 1960. In 1962 he ran for the U.S. Senate against Benjamin Dillingham II, son of a prominent Hawaii family, and won by nearly 70 percent of the vote. In 1968 he won by an even greater margin. And in 1974 his third-term victory seems assured.

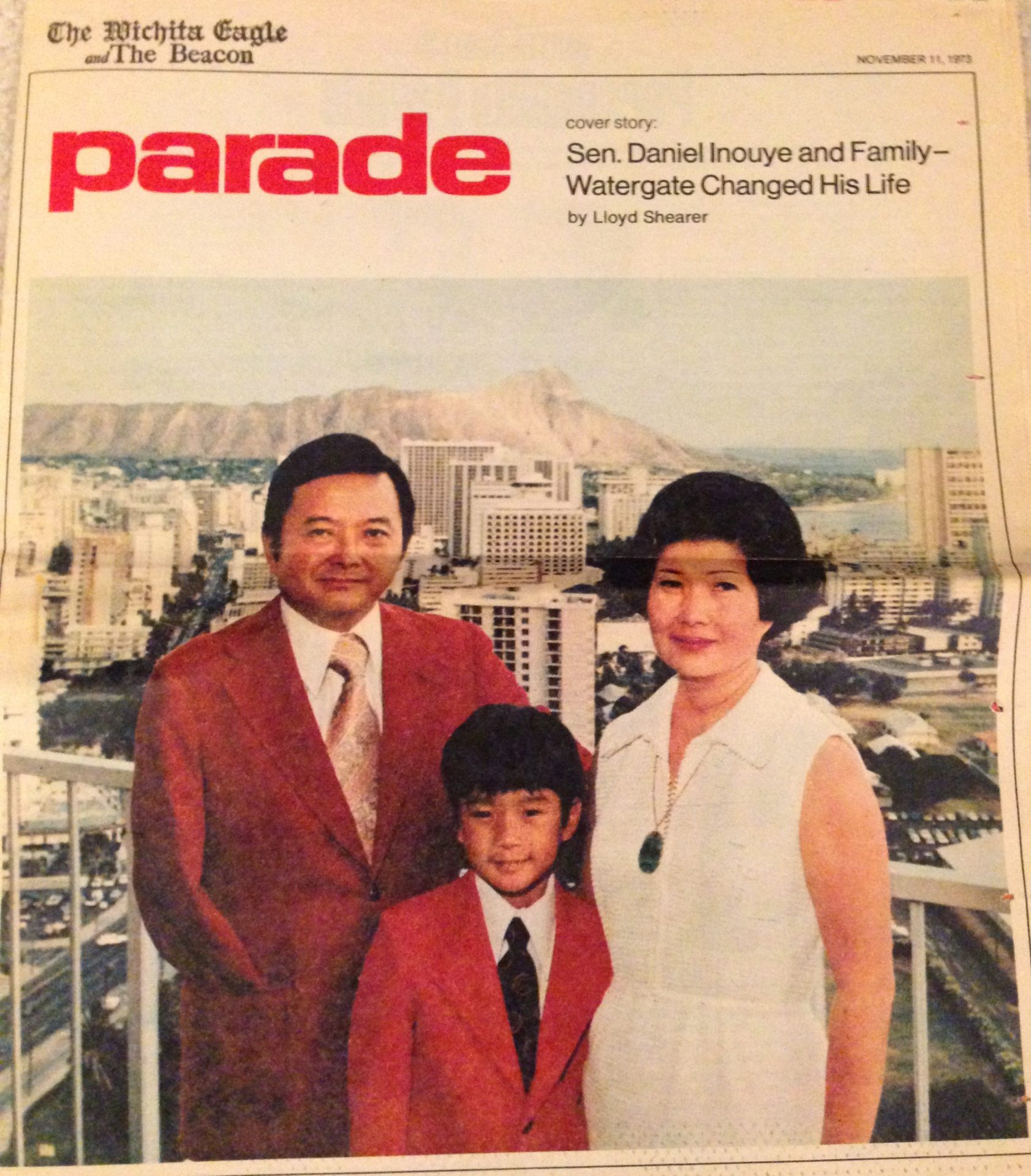

The Senator and his wife have only one child, 9-year-old son Danny, “who came late in our lives, when we both were 40,” Inouye points out, “and I try to spend as much time with him as possible. We live in Bethesda, Md., and we feed tropical fish and look after squirrels, chipmunks and birds together.

Entertain little

“My wife and I don’t entertain very much. In the eight years we’ve had our Bethesda house, we’ve had two receptions, both of them neighborhood receptions. I don’t give parties for ambassadors or other Senators or visiting dignitaries. I need time to be alone with my family, to collect my thoughts, to think things through.”

When asked how he would describe himself politically, the Senator says he’s a moderate Democrat. He regrets having supported the Vietnamese war, attributes it in large part to his friendship with Lyndon Johnson “and the conditions of the times.”

He used to wear an artificial arm “when I first got out of the hospital,” and asks, “Did you know that Phil Hart [Democratic Senator from Michigan] and Bob Dole [Republican Senator from Kansas] and I were all in the same veterans hospital in Battle Creek, Mich., after the war? Prosthetics weren’t very well developed back then. Wearing an artificial arm in tropical Hawaii was uncomfortable and sticky and smelly. And I didn’t need it to practice law, so I took it off; and I just haven’t worn one since.”

Leads poll

This past August, a survey by the Gallup Poll people revealed that all seven members of the Watergate committee were favorably regarded by a majority of Americans, with some achieving a nationwide name awareness.

In that same survey, the Gallup pollsters asked their subjects to rate the seven committee members on a 10-point attitude scale. Daniel Inouye came in first with a 84 percent favorable rating. Sam Ervin was second with 81 percent, Howard Baker third with 78.

Those statistics faithfully reflect the sensational popularity climb of Daniel Inouye in the past six months from island Senator to national celebrity.

Where he goes from here he declines to speculate. His reelection in 1974 seems a certainty. The Republicans in Hawaii may not even offer token opposition. Inouye maintains that U.S. Senator is as high an office as he cares to achieve. Certainly he has brought great honor to his native state by his Horatio Alger rise. But politics has an insidious way of infecting men with its ambition virus. And it would surprise few people if the Democratic National Convention in 1976 nominated him as its candidate for the Vice Presidency.

© 1973 Parade. Reprinted by permission.